Last month we reviewed and expanded on some issues in setting limits for rinse samples. This month we’ll cover issues related to performing both swab and rinse sampling in the same protocol run. In doing so, considerations relating both to a separate sampling rinse (SSR) and to a grab sample of the final cleaning procedure rinse will be discussed.

Initial considerations

But first, I should state that the ideal way (and most accurate and precise way) to do both swab and rinse sampling for a protocol is to do them in separate (distinct) protocol runs. That is, if I require three protocol runs, to avoid the results from one sampling method affecting the results of the other sampling method, I would perform three runs just doing swab sampling and also perform another three runs just doing a separate sampling rinse (SSR). By doing that I avoid the issue of that first sampling procedure interfering with the second sampling procedure. If this were my strategy and if all surfaces involved both sampling types, I would try to do the three runs with swab sampling first, because if there were problems with my cleaning procedure, unacceptable results would more likely show up with swab samples. On the other hand, if there were areas (like pipes) which were only effectively sampled by rinsing, this would complicate things such that I may want to alternate swab and rinse runs. Note that this concern may not apply if (for whatever reason) I am only doing rinse sampling (and not swab sampling) for the piping, and the rinse solvent is not contacting other equipment surfaces.

For example, if I do swab sampling before a separate sampling rinse, I am likely to remove residues (which would otherwise be detected in the subsequent SSR). This might make the actual M4c results be lower, and therefore make it more likely for the protocol to pass for the calculated L4c limit. Now in this situation, I might judge that if I set limits appropriately (see last month’s Cleaning Memo) and both the swab samples and rinse samples pass, I am probably okay. The reason for this judgment is that swab samples focus on the worst case locations, whereas the rinse sample essentially averages the values from each equipment surface (which includes both difficult-to-clean locations and easy-to-clean locations). Therefore, if I picked the worst case locations on a sound basis, I am less concerned that the residues removed from the swabbed locations would have seriously affected the rinse M4c values. However, be aware that this is something where you should have confidence in that judgment.

A more complicated approach

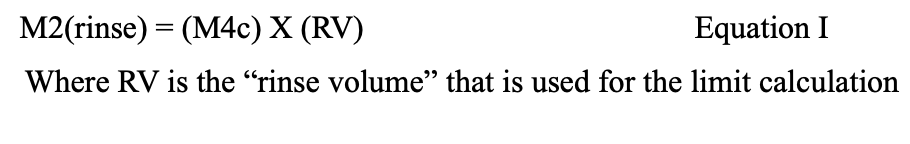

If we wanted to additionally evaluate results where the same surfaces are sampled with swab sampling followed by a separate sampling rinse, then there is another more complex option that some have used. This is more complicated because it involves combining the data from the swab samples with the data from the rinse sample to determine a possible combined total carryover. This has to be done carefully! The “total combined carryover” is the sum of the swab M2 values (based on stratified sampling principles) and the rinse M2 value, which should then be compared to the L2 limit. This is essentially a variation of “stratified sampling” approach for determining compliance (see Cleaning Memos of March and April 2010). For situations where there is only one rinse sample for the entire equipment, the “M2 rinse” value is determined as follows:

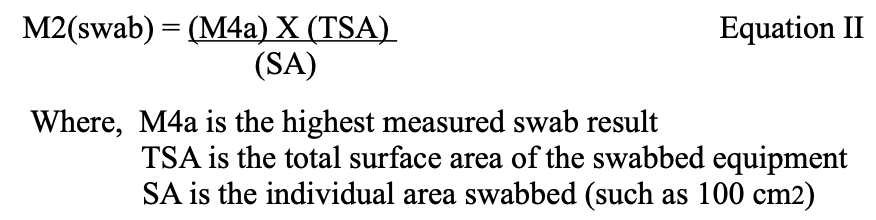

The simplest approach for calculating the total “M2(swab)” is to just utilize the highest M4a or M4b value and convert that value to determine a maximum possible M2(swab) value. That is done as follows (using in this example M4a rather than M4b):

The maximum possible M2 is the sum of the result of Equation I and of the result of Equation II. That sum is then compared to the overall L2 limit. Yes, doing it this way certainly may overstate the amount of residue carried over; but if that overstated amount is less than the calculated L4 limit, then I am happy.

This analysis of the swabbing results can be made more complicated by considering the results for each swabbed segment, much as is done in stratified sampling for equipment segments; however, that evaluation is more complex and may not be worth the effort.

SSR before swabbing in same protocol run

On the other hand, if I do a separate sampling rinse before the swab sampling, I have effectively reduced the residues that could be detected by swab sampling. A large portion of the residues in those worst-case locations that I would swab may have been effectively reduced. While they may have been picked by the separate sampling rinse, the large volume of sampling water used in the separate sampling rinse may obscure the higher level of residues in the worst-case locations. This option should generally be avoided.

Using a “rinse sample” of the process rinse

I should state upfront that this is what most companies do if they want to have the swab sampling and rinse sampling done in a given protocol run. If this is not “technically” correct, why is this acceptable? The simple reason is taking a rinse sample of the final portion of the process rinse does not interfere with residues left on the equipment surfaces that are then swabbed after completion of that process rinse; the residues left on the equipment surfaces should not change by doing a rinse sample in this way. Furthermore, the residue concentration (M4c) in the final portion of the process rinse should not be greater than the residue concentration if I were to perform a separate sampling rinse. That is, it is not likely that I would measure 0.7 ppm in the final portion of the process rinse and, if I were to immediately perform a separate sampling rinse and collect the entire amount of that SSR, that the concentration in the SSR would be greater than 0.7 ppm. This is the reason why in setting limits for a grab rinse sample of the final process rinse it is important to make a reasonable estimate of the volume of water used for the SSR in calculating the L4c value for the rinse sample (see Cleaning Memos of January 2009 as well as an earlier version in October 2005 for more on setting limits for grab samples of the process rinse).

Additional considerations

Furthermore, while I generally recommend that the grab sample be the final portion of the process rinse, it is not necessarily a requirement. If I took a sample well before the final portion of the process rinse and sent that to the lab for analysis for residues, it is likely that the M4c value in that earlier process rinse sample would be greater (or at least no less than) the M4c value in the final portion of the process rinse. So, as long as that earlier process rinse sample was less than my L4c limit, I should have confidence that I was achieving my calculated limit. The concern about taking a grab sample earlier in the final rinse process is if the M4c value exceeds the L4c limit, I have no data to show that my process rinse is effective unless I were to also collect and analyze a later portion of the process rinse. While collecting such earlier data may be helpful in design studies (Stage 1 of a lifecycle approach), it probably should be avoided in an actual validation protocol.

That said, it is also important to point out that the final portion of the process rinse is not necessarily the exact last 100 mL as the rinse water exits the equipment; if one tries to do that it is possible that the last portion will be missed (and I would have no sample at all). So it could be a slightly earlier sample (realizing that if that earlier portion passed, I would still be satisfied). However, if the final process rinse were 100 L, I should avoid trying to take my 100 mL sample for analysis after passing only 50 L though the equipment.

If this seems confusing (as it might), you might try “imagining” the steps in using both swab sampling and rinse sampling and how that combination might affect the collected data.

Copyright © 2023 by Cleaning Validation Technologies