The shared surface area between two products is one of the key factors used in a typical carryover calculation to determine limits for cleaning validation. The value for the shared surface area (typically in square centimeters or square inches) is in the denominator of a carryover calculation; therefore the larger the shared surface area, the lower the limit.

While I generally like to talk about the shared surface area, there are several variations which I have seen used which are not the actual shared surface area, but could be values above the actual shared areas. The fact that those values are above the actual shared area makes the calculated limits lower, thus representing a worst case and therefore acceptable from a compliance perspective.

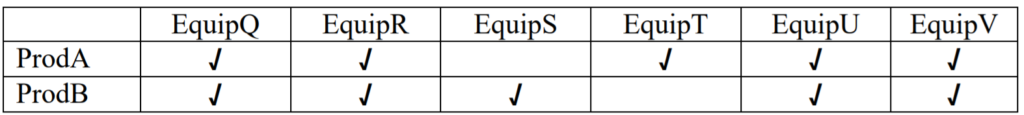

Before we explain the alternatives, we’ll first consider the technically correct case. If the cleaned product (ProdA) and the subsequently manufactured product (ProdB) are made on exactly the same equipment, then life is simple – the shared surface area is the product contact surface area of the equipment train. If not all equipment is shared, then the actual shared surface area is the relevant surface area to use. Let’s supposed the equipment used for the two products is as given in the table below, with the check marks indicating which equipment is used for which product.

In this situation, the actual surface area shared is from the sum of the areas of EquipQ, EquipR, EquipU and EquipV. EquipS and EquipT are not shared between the two products, so their surface areas are excluded. As an aside, you might ask how limits for EquipT are set in the cleaning of ProdA. The answer is simple – are there additional products (for example, ProdC) which share equipment with ProdA? If so, then the limits for EquipT are established based on the shared equipment between ProdA and ProdC. If EquipT is only used for ProdA, then set limits for EquipT as you would for dedicated equipment.

Okay, that is the technically correct approach. Now we’ll consider two other acceptable approaches used by some companies. One approach is just to use the actual surface area of the cleaned product for calculation of limits. In the case of ProdA and ProdB as shown in the table above, the limit for cleaning of ProdA (the cleaned product) would include the surface area of the entire train of ProdA. That is, it would include the sum of the surface areas of EquipQ, EquipR, EquipT, EquipU and EquipV. Wouldn’t that give a “shared” area above the actual shared area between ProdA and ProdB? Yes it would, and it would result in a calculated limit below that of a calculation using the actual shared area. Therefore, it would be a worst case, and should be acceptable from a compliance perspective. You might then ask, “Why would someone use this approach?” The answer to that is that it simplifies having to determine what equipment is actually shared, particularly for those not using validated software for calculation of limits.

Now for the second option that some companies use. Again I will illustrate this with the two products in table above. In this approach, the total actual equipment surface area for each product is calculated, and the value used for the surface area in the calculation is the lower of the surface area of the two individual products. For clarification, this is not the actual surface area shared. So for ProdA, the actual surface area would be the sum of the areas of EquipQ, EquipR, EquipT, EquipU and EquipV. And for ProdB, the actual surface area would be the sum of the areas of EquipQ, EquipR, EquipS, EquipU and EquipV. By using the lowest surface area of either product train, I am assured that the value used will be no lower than the actual shared surface area (another way to state this is that the area used for my calculation will be either the same or greater than the actual shared surface area.

I have illustrated this using only two products. However, the principles can be utilized for situations where three, four, or even more products share some (but not all) equipment.

These alternative approaches (alternatives to the use of the actual shared surface area) may drive limits lower. Depending on the types of products, this may or may not make cleaning validation more difficult. If limits are driven too low, then it is always possible to fall back to the approach of using the actual shared surface area, thus increasing the calculated limits to some extent.